Lincoln ordered the largest mass execution in U.S. History: President's Day Special

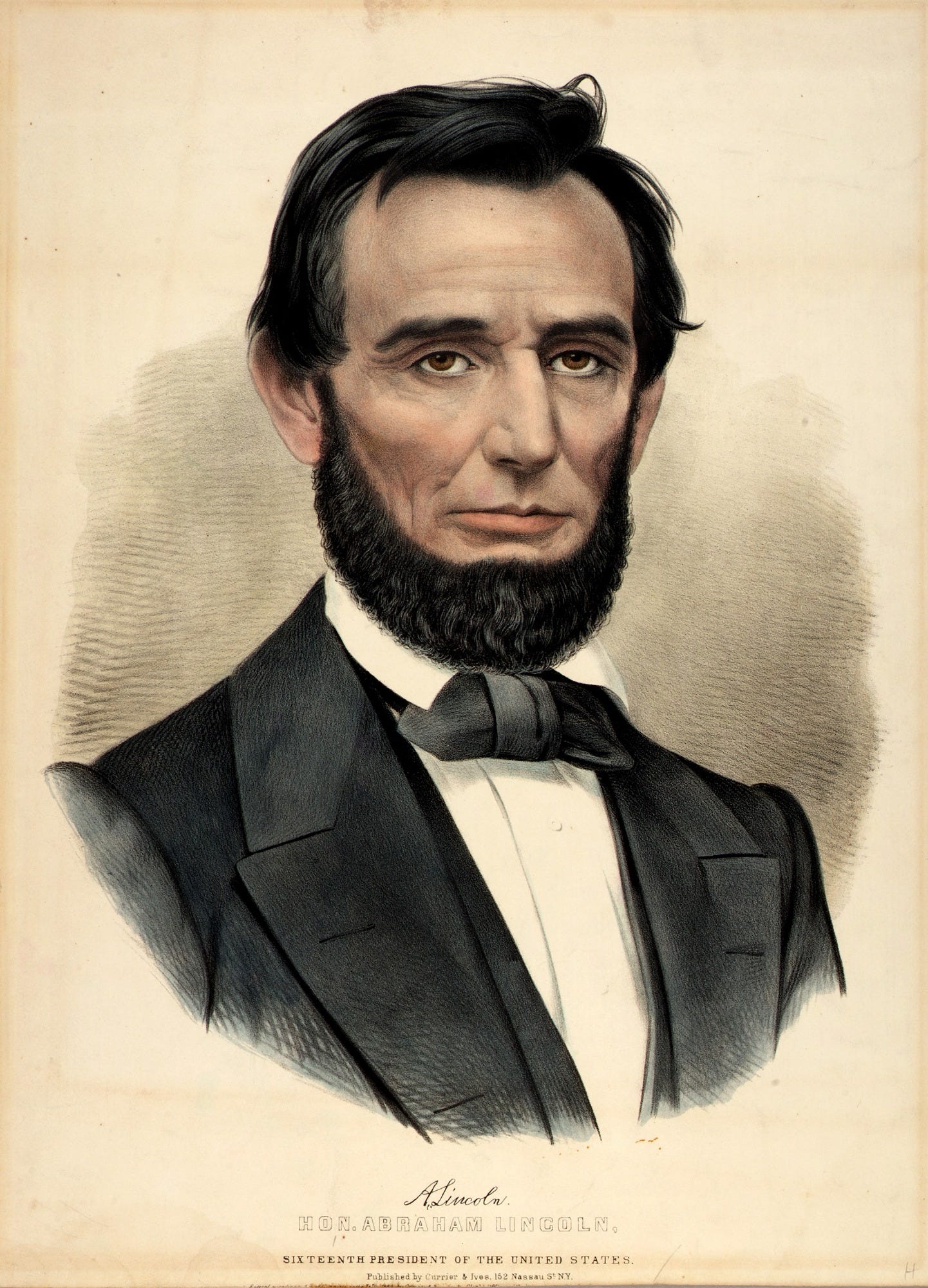

The President ordered the mass execution of 38 Dakota Native Americans but spared Confederate leaders—revealing a stark double standard.

On December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota, the U.S. government carried out the largest mass execution in American history. 38 Dakota Sioux men were hanged on the orders of President Abraham Lincoln following the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. This execution, conducted in front of a cheering white crowd, was a direct result of years of broken treaties, land theft, and federal neglect that left the Dakota people starving and desperate.

The Context: Betrayal and Starvation

Minnesota, a young frontier state in 1862, was rapidly expanding white settlement at the direct expense of the Dakota people. In previous treaties, the Dakota had ceded vast amounts of land to the U.S. government in exchange for annual payments and supplies. However, that summer, the government failed to deliver the promised resources, leaving the Dakota to starve. One callous trader, Andrew Myrick, even suggested, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.” When Myrick was later found dead, his mouth was stuffed with grass—a stark symbol of the desperation that led to war.

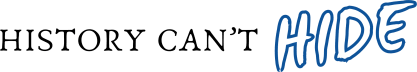

Under the leadership of Little Crow, the Dakota, pushed to their limits, launched attacks on white settlements in August 1862. Over the course of six weeks, approximately 490 settlers were killed, including women and children. The U.S. government quickly crushed the uprising, with Henry Hastings Sibley, Minnesota’s first governor, capturing over 2,000 Dakota people. A military tribunal sentenced 303 Dakota men to death in rapid, deeply flawed trials—some lasting less than five minutes.

Lincoln’s Role: A Calculated Decision

Despite his reputation as the Great Emancipator, Lincoln’s role in this execution remains a glaring contradiction in his legacy. He personally reviewed the cases and commuted 265 of the sentences, but approved the executions of 39 men (one was later suspended). His reasoning? He claimed to be distinguishing those guilty of rape and murder from those who merely participated in battle. However, the trials lacked due process, with many of the accused receiving verdicts in mere minutes. Even Lincoln acknowledged the flawed nature of these trials but saw little alternative given the mounting political pressure.

Major General John Pope, the Commander of the Military Department of the Northwest, made clear the vengeful intentions behind the proceedings, instructing Sibley that the Dakota should be treated as “maniacs or wild beasts and by no means as people with whom treaties or compromises can be made.” This directive reinforced a legal farce, where guilt was presumed, and executions were the expected outcome. The rushed convictions and Lincoln’s reluctant approval reflected the broader sentiment of white Minnesotans, who demanded blood in retribution for the war.

Lincoln, despite his legal background, accepted the findings of a military court that ignored even the most basic legal protections. He may have viewed his decision as a compromise between justice and appeasing a furious white settler population, but in doing so, he sanctioned a purposely corrupt process. If Lincoln had truly sought fairness, he could have demanded new, legitimate trials rather than sorting through already questionable verdicts. Instead, he prioritized political expediency, leaving behind a tragic legacy in Minnesota’s history.

The Execution: A Public Spectacle

On the morning of December 26, 1862, a massive gallows was erected in Mankato’s public square. The 38 Dakota men, bound in shackles, chanted and sang in their final moments. A large crowd of white spectators gathered to watch as the trapdoors were released, sending the men to their deaths simultaneously. It was an execution on a scale unseen in American history. Two more Dakota leaders, Shakopee (Little Six) and Medicine Bottle, were captured in Canada, forcibly returned to U.S. custody, and later executed at Fort Snelling in 1865, extending the government’s retribution beyond the initial mass hanging.

While Lincoln’s clemency saved some, his actions still reinforced the U.S. government's violent suppression of Indigenous resistance. In the following months, the remaining Dakota were expelled from Minnesota, exiled to reservations in South Dakota and Nebraska. Congress further punished the Dakota by annulling all treaties with them, ensuring their lands remained in white hands.

Names of the Victims

Tipi-hdo-niche (Forbids His Dwelling)

Wyata-tonwan (His People)

Taju-xa (Red Otter)

Hinhan-shoon-koyag-mani (Walks Clothed in an Owl’s Tail)

Maza-bomidu (Iron Blower)

Wapa-duta (Scarlet Leaf)

Wahena (Translation Unknown)

Sna-mani (Tinkling Walker)

Radapinyanke (Rattling Runner)

Dowan-niye (The Singer)

Xunka-ska (White Dog)

Hepan (Family Name for a Second Son)

Tunkan-icha-ta-mani (Walks With His Grandfather)

Ite-duta (Scarlet Face)

Amdacha (Broken to Pieces)

Hepidan (Family Name for a Third Son)

Marpiya-te-najin (Stands on a Cloud / Cut Nose)

Henry Milord (French Mixed-Blood)

Dan Little (Chaska Dan, Family Name for a First Son) (This may be We-chank-wash-ta-don-pee, who had been pardoned and was mistakenly executed when he answered to a call for “Chaska”)

Baptiste Campbell (French Mixed-Blood)

Tate-kage (Wind Maker)

Hapinkpa (Tip of the Horn)

Hypolite Auge (French Mixed-Blood)

Nape-shuha (Does Not Flee)

Wakan-tanka (Great Spirit)

Tunkan-koyag-i-najin (Stands Clothed with His Grandfather)

Maka-te-najin (Stands Upon Earth)

Pazi-kuta-mani (Walks Prepared to Shoot)

Tate-hdo-dan (Wind Comes Back)

Waxicun-na (Little Whiteman) (This young white man, adopted by the Dakota at an early age and who was acquitted, was hanged, according to the Minnesota Historical Society U.S.-Dakota War website.)

Aichaga (To Grow Upon)

Ho-tan-inku (Voice Heard in Returning)

Cetan-hunka (The Parent Hawk)

Had-hin-hda (To Make a Rattling Noise)

Chanka-hdo (Near the Woods)

Oyate-tonwan (The Coming People)

Mehu-we-mea (He Comes for Me)

Wakinyan-na (Little Thunder)

(Minnesota Historical Society, “U.S.-Dakota War of 1862”)

Letter from Hdainyanka to Chief Wabasha written shortly before his execution:

"You have deceived me. You told me that if we followed the advice of General Sibley, and gave ourselves up to the whites, all would be well; no innocent man would be injured. I have not killed, wounded or injured a white man, or any white persons. I have not participated in the plunder of their property; and yet to-day I am set apart for execution, and must die in a few days, while men who are guilty will remain in prison. My wife is your daughter, my children are your grandchildren. I leave them all in your care and under your protection. Do not let them suffer; and when my children are grown up, let them know that their father died because he followed the advice of his chief, and without having the blood of a white man to answer for to the Great Spirit."

Source: Isaac V. D. Heard, History of the Sioux War and Massacres of 1862 and 1863, NY: Harper & Bros., 1863A Stark Contrast: Lincoln and the Confederacy

One of the most unsettling aspects of this event is Lincoln’s contrasting approach to Confederate rebels. After the Civil War, despite the deaths of over 400,000 Union soldiers, Lincoln did not order the execution of a single Confederate official or general for treason. The only Confederate to face capital punishment was Henry Wirz, the commander of Andersonville Prison, who was hanged for war crimes, not for rebellion. Yet Lincoln sanctioned mass execution for Indigenous men fighting for their land, highlighting a brutal double standard in U.S. history.

Civil War Heroes Turned Villains Against Native Americans

Lincoln wasn’t alone. Many of the same figures celebrated as heroes of the Civil War went on to wage brutal campaigns against Native Americans, furthering U.S. expansion at the cost of Indigenous lives and sovereignty.

General William Tecumseh Sherman, famed for his “March to the Sea,” applied his scorched-earth tactics not just against the Confederacy but against Native Americans in the West. As head of the U.S. Army after the Civil War, Sherman saw Native resistance as an obstacle to be crushed, writing: "The more we kill this year, the less we will have to kill next year." He led ruthless campaigns against the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Comanche, systematically destroying their food sources, burning villages, and ensuring their forced removal to reservations. The mass slaughter of buffalo, the primary resource for many Plains tribes, was a deliberate strategy to starve Native communities into submission.

Even Ulysses S. Grant, the revered Union general and later U.S. president, played a direct role in Native displacement. Grant’s so-called Peace Policy was meant to curb corruption in Indian affairs, but it also enforced forced assimilation and reservation confinement. Under his leadership, the U.S. government illegally seized the Black Hills from the Lakota after gold was discovered there, violating previous treaty agreements. This betrayal led to the Great Sioux War of 1876, culminating in infamous conflicts such as the Battle of the Little Bighorn and, later, the Wounded Knee Massacre—one of the deadliest attacks on Native Americans in U.S. history.

Reassessing the Legacy of Civil War Leaders

The myth of Lincoln and the Union Army as universally benevolent or racially progressive ignores how their victories in the Civil War aligned with economic and political interests that benefited white Northern elites. While abolitionists sought to dismantle slavery, many of the political and industrial forces behind the Union cause saw emancipation as a means to consolidate national power and further economic and land expansion.

At the same time, the government’s commitment to Indigenous sovereignty remained nonexistent. The land occupied by Native nations was viewed as an obstacle to economic growth and westward expansion, and the same military leaders celebrated for preserving the Union soon turned their focus to clearing Indigenous people from their lands. This pattern reflects the concept of interest convergence: the idea that marginalized groups only gain rights when those rights align with the interests of those in power.

Lincoln’s reluctance to take a harsher stance against the Confederacy contrasted sharply with his willingness to execute 38 Dakota men, underscoring how justice was often applied selectively. Even after the Civil War ended, the Union's priorities quickly shifted to subduing Indigenous nations, using many of the same military strategies deployed against the South. While the defeat of the Confederacy is rightly seen as a victory for justice, it also laid the foundation for a new chapter of oppression—one in which Native Americans bore the brunt of America's growing hunger for land and resources.

A thank you to my readers

This article was partially conceived as a reader request from

, thank you. If there is a topic you want me to cover, just let me know in the comments!References

Chomsky, Carol. The United States-Dakota War Trials: A Study in Military Injustice. Stanford Law Review, 1990.

Haymond, John A. The Infamous Dakota War Trials of 1862: Revenge, Military Law, and the Judgment of History. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2016.

Bachman, Walt. Northern Slave, Black Dakota: The Life and Times of Joseph Godfrey. Bloomington, MN: Pond Dakota Press, 2013.

Blakemore, Erin. Native Americans Have General Sherman to Thank for Their Exile to Reservations. HISTORY, July 11, 2023. Originally published November 13, 2017.

Mustful, Colin. The Largest Mass Execution in U.S. History: A Timeline to Understand How Abraham Lincoln Ordered the Execution of 38 Dakota Men. Reclaiming Mni Sota, December 26, 2020.

Foner, Eric. The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010.

Nichols, David A. Lincoln and the Indians: Civil War Policy and Politics. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1978.

Prucha, Francis Paul. The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984.

Ostler, Jeffrey. Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019.

Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1970.

Finkelman, Paul. "I Could not Afford to Hang Men for Votes—Lincoln the Lawyer, Humanitarian Concerns, and the Dakota Pardons." William Mitchell Law Review 39, no. 2 (2013): Article 2.

Heartbreaking. Utterly heartbreaking. Thank you for this. So agree with Stephen Jules Otis Career Rubin - European history and its very much alive legacy is monstrous. Wherever they went they maimed, enslaved, murdered and dispossessed. Where was and is the moral compass?! I’m Irish and I know what I’m talking about unfortunately. But wow the story is not over. They caused turmoil and left turmoil as they retreated to their grand mansions. But thanks to Historians like you they will not escape the shame. The truth will set us all free.

such an anem wonderful history this nation has ..sadly for as long as most people don't want to acknowledge the true history of Europeans and their lineage from arrival of taking what they want manipulating facts lying stealing cheating or just taking eliminating enemies attacking other animals esp bison to destroy natives to get land ...in short doing anything with no restraints moral compass nor regulation often to take whatever they want so of course this current lunatic gubbament is talking about buying things not for sale changing names etc....amd for as long as the history isn't acknowledged the present will continue to be nothing at all great but more horrible behavior from a now very much not growing but dying splitting apart destroying itself short lived empire... pathetic sad avoidable