This Real Person Was Just Like the Villain in “Sinners”—Actually, He Was Worse

Before Ryan Coogler’s “Sinners” imagined a vampire stealing Black culture and lives, Jim Jones did it for real ... and over 900 people died.

Ryan Coogler's new film "Sinners" has captivated audiences with its brilliant blend of horror, social commentary, and historical exploration. Critics celebrate Michael B. Jordan's dual performance as twins Smoke and Stack in 1930s Mississippi, but it's Jack O'Connell's Irish vampire Remmick who sparks the most intriguing conversations about cultural appropriation and racial dynamics in America.

*Spoilers for “Sinners” movie below*

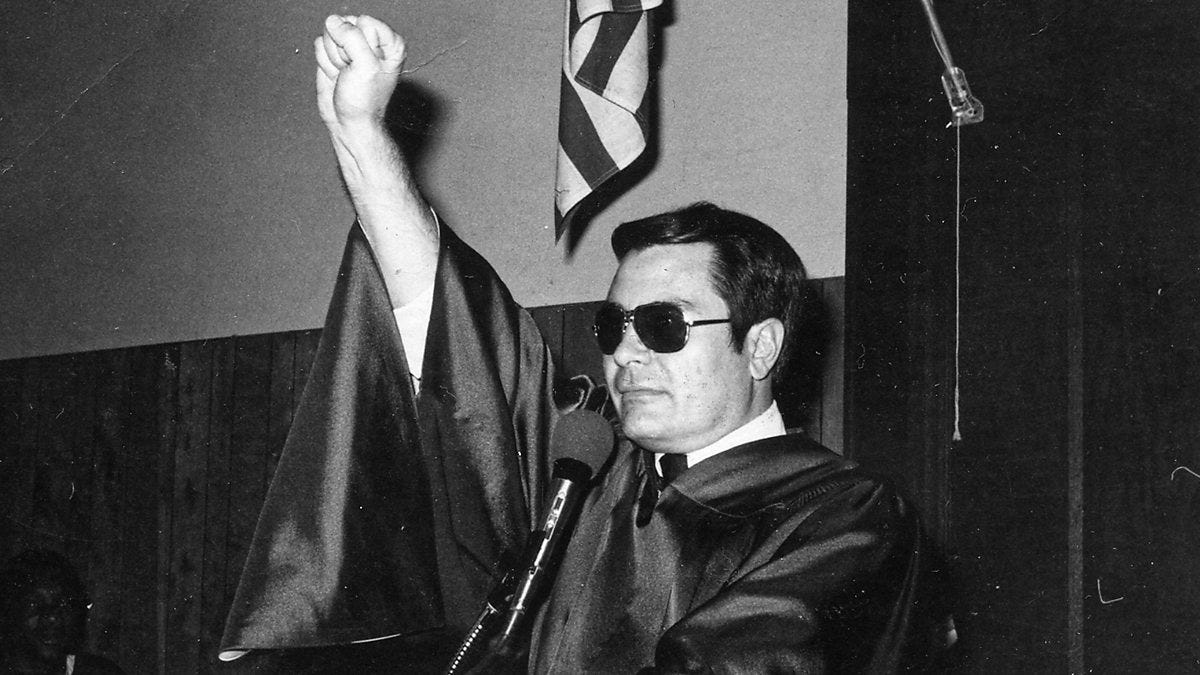

Now imagine a real-life figure whose manipulation of Black communities mirrored Remmick's predatory tactics with eerie precision. A man who, like the fictional vampire, positioned himself as an ally to Black Americans before ultimately leading them to their deaths. That person has a name, and his name was Jim Jones.

I'm fighting to document stories like those of the vicitms of Jonestown before they're erased entirely—and I need your help!

With no corporate backing or wealthy sponsors, this work depends entirely on readers like you. If everyone reading this became a paid subscriber, I could investigate these institutional reckonings full-time, but right now less than 4% of my followers are paid subscribers.

If you believe in journalism that tracks moral accountability when others look away, please consider a paid subscription today!

Who Was Jim Jones?

"Don't drink the Kool-Aid."

We've all heard this warning against blind obedience to charismatic leaders. What many don't realize is this ubiquitous phrase originated from one of America's most horrific tragedies. The 1978 Jonestown massacre saw over 900 people die after consuming cyanide-laced Flavor Aid (not actually Kool-Aid) at the command of cult leader Jim Jones.

Born in 1931 in rural Indiana during the Great Depression, Jones grew up in a household with a disabled World War I veteran father and a working mother. Despite non-religious parents, he developed a strange fascination with the Bible, often holding makeshift "services" for neighborhood children.

Jones became an ordained Methodist minister in the 1950s but quickly grew frustrated with mainstream Christianity's comfortable relationship with segregation. He established his own church, eventually known as Peoples Temple, focusing on racial integration, social justice, and radical socialism. Or so he claimed.

His Peoples Temple gained momentum in Indianapolis with racially integrated congregations, soup kitchens, and nursing homes. Fearing nuclear war, Jones relocated his growing flock to Ukiah, California in the mid-1960s, before expanding to San Francisco in the early 1970s.

The charismatic preacher gained political influence in California, mobilizing his diverse congregation to support progressive candidates. Temple members staffed phone banks, distributed campaign literature, and showed up en masse at political rallies. Jones received an appointment to San Francisco's Housing Authority in 1976 and cultivated relationships with prominent political figures, including future mayor Willie Brown and First Lady Rosalynn Carter.

Behind this progressive façade lurked increasingly troubling dynamics. Temple members faced physical punishment, public humiliation, and exploitation. Jones staged fake faith healings, claimed to be the reincarnation of figures like Lenin and Jesus, and demanded absolute loyalty. When Congressman Leo Ryan visited to investigate allegations of abuse, Jones ordered his murder. Within hours, Jones then forced or coerced over 900 followers—including nearly 300 children—to drink cyanide-laced Flavor Aid in what he called 'revolutionary suicide.' The congressman and five others were shot to death at the airstrip while attempting to leave with defectors.

The Cultural Vampire

In "Sinners," Remmick fixates on Sammie's transcendent musical ability, a gift so powerful it summons spirits from both past and future. The vampire doesn't simply appreciate this talent. He covets it, seeking to harness it while offering false promises of freedom from racism. Richard Lawson notes in his Vanity Fair review that Remmick "wants to use Sammie's skills to summon the spirits of his lost community," attempting to appropriate a spiritual power that isn't his to command.

Jones similarly recognized the spiritual power in Black churches and set out to appropriate it. Despite his white, non-religious upbringing in Indiana, he strategically adopted the preaching style of Black Pentecostal ministers to build his following.

His epiphany came after visiting Father Divine's Peace Mission in Philadelphia, a Black-led religious movement with an integrated congregation. Jones became obsessed with Divine's success, making multiple trips to the Peace Mission between 1958 and 1965. The change in Jones after these visits was dramatic. He began copying Divine's theatrical preaching style, adopting his methods of faith healing (which Jones faked using sleight of hand), and replicating Divine's organizational structure. Jones instructed his followers to call him "Father" and his wife "Mother," just as Divine's followers did. He established communal living arrangements, free meal services, and adoption programs mirroring the Peace Mission's operations.

Jones wasn't content to merely admire Divine's accomplishments. After Father Divine's death in 1965, Jones claimed he was Divine's reincarnation and attempted a hostile takeover of the Peace Mission. He traveled to Philadelphia with busloads of Temple members, declaring to Divine's widow that Father Divine's spirit had entered his body. When this brazen takeover failed, Jones launched a smear campaign against Mother Divine, falsely claiming she had made sexual advances toward him.

This cultural vampirism extended to Jones's broader religious practice. Though he privately admitted his atheism to close associates, he publicly performed as a faith healer and prophet. He used his knowledge of his congregation's private affairs, gleaned through an extensive spy network, to feign clairvoyance. He planted faithful followers in the audience who would pretend to be healed of cancer, secretly hiding raw chicken organs in the bathroom to be "passed" during the service as evidence of removed tumors.

The False Ally

What makes Remmick compelling is his genuine understanding of oppression. As an Irishman who lived through centuries of British colonization, he can speak authentically about marginalization. "His nationality tells a deeper story about the Irish community's initial experience in the United States and abroad, its complex relationship with foundational Black Americans," explains Raquel Harris in The Wrap. The villain knows what it feels like to be oppressed, giving his betrayal added weight.

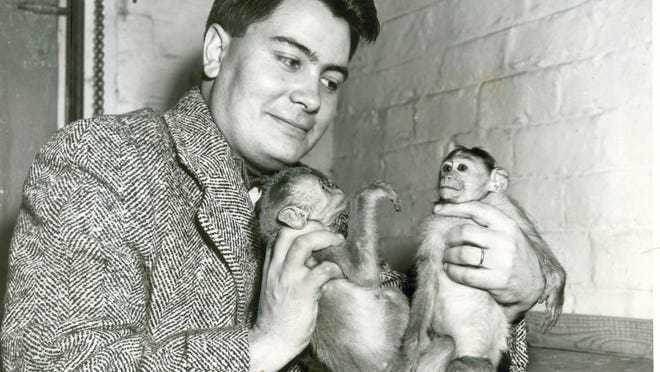

Jones positioned himself as a bridge-builder in segregated 1950s Indianapolis. While mainstream churches remained rigidly segregated, Jones created an integrated sanctuary and vocally supported civil rights causes. He and his wife became the first white couple in Indiana to adopt a Black child in 1961, the same year Freedom Riders were being brutally attacked in Alabama for attempting to desegregate interstate buses.

Anonymous threats arrived at the Jones home. Some notes stated that people were "praying for the death of their black son." His integrated family, which eventually included additional adopted children of Korean and Native American descent, became a powerful symbol of his commitment to racial equality. Years later, his adopted Black son reflected that despite all the suffering his father caused, Peoples Temple "allowed me, as a black man, to hold my head up high."

The Temple's social welfare programs specifically targeted underserved Black communities. Temple member Glen Hennington explained why this was particularly impactful in the late 1960s: "Robert Kennedy had been killed. Malcolm had been killed. Martin Luther King had been killed. So you're looking at a period of time of civil rights consciousness when there were those in this country that were tryin' to stomp [racism] out, and you had somebody here who was not only speakin' about it, but as far as I could see, it was being demonstrated before my very eyes."

For interracial couples like Vernon Gosney and his Black wife, who had been refused marriage by other churches (interracial marriage remained illegal in some states until 1967), Peoples Temple offered rare acceptance. "We were not accepted. Her family didn't accept me. My family didn't accept her, and it was really important to us, to have a place to be in a place where we were accepted and embraced and celebrated..."

The truth beneath both men's allyship eventually surfaced. Remmick weaponized his whiteness to become "the thing he hated most by forcing his way of life onto others." Jones likewise used his racial justice platform primarily to advance his own authority and communist ideology. He once bluntly admitted about his integration efforts: "There's no way I'm going to politicize these f——rs if I can't get them to sit together."

Jones's personal convictions about racial equality seemed genuine at times. His actions, however, revealed they were subordinate to his desire for control. His "Rainbow Family" of adopted children from various racial backgrounds became props in his narrative of enlightened leadership. Even as he condemned racism in American society, he created a system of total control within his congregation. Physical abuse, sexual exploitation, and psychological manipulation became commonplace.

The opportunistic nature of Jones's racial politics is striking. In Indianapolis, he preached integration. In California, he courted support from Black radical groups with militant rhetoric. In Guyana, he invoked the specter of American racism to discourage followers from returning to the United States. His stance on race adjusted at each stage to maximize control over his followers rather than address racial injustice.

The Cult's Ultimate Trap

The most disturbing parallel between Remmick and Jones lies in how they offered "freedom" through what amounted to death. In "Sinners," Remmick presents vampirism as liberation from racism, claiming it offers "immortality, freedom, and escape" from oppression. He specifically warns the protagonists that the KKK plans to attack their juke joint at dawn, positioning his vampiric "gift" as the only alternative to racist violence.

This "freedom" requires surrendering one's humanity and joining Remmick's undead collective. As Coogler's film makes clear, this isn't liberation. It's a different form of subjugation, one that literally feeds on the victims of oppression.

Jones similarly promised liberation through his socialist utopia. He frequently told his congregation that Jonestown was a "rainbow family" free from American racism. "We have 27,000 acres undertaking abroad in a mixed society, black president, but a beautifully racially-inclusive society," Jones once boasted in a radio interview. For many of his followers, particularly older Black members, the move to Guyana unconsciously echoed Marcus Garvey's back-to-Africa movement, a promise of escape from American racism.

The reality of Jonestown proved far different. Members worked long hours in tropical heat, attempting to make the land productive enough to sustain the community. Loudspeakers constantly broadcasted Jones's rambling speeches. After exhausting workdays, members attended mandatory evening meetings where Jones promoted communist ideals while stoking paranoia about external threats.

Jones conducted what he called "White Nights," mass suicide rehearsals where members drank what they were told was poison (later revealed to be harmless) as a test of loyalty. These drills directly foreshadowed the community's eventual fate. Jones called this practice "revolutionary suicide," a term borrowed from Black Panther Huey Newton but twisted to serve Jones's needs.

When the utopia Jones promised failed to materialize in Guyana, he orchestrated the mass murder-suicide, convincing his followers that death was preferable to returning to racist America. The Jonestown massacre claimed the lives of over 900 people, approximately 70% of whom were Black. Like the fictional Remmick, Jones first offered escape from racism, then led his followers to destruction when his utopian vision faltered.

More Than Fiction

Ryan Coogler has crafted in Remmick a villain who represents broader themes of cultural theft and colonization, one who understands oppression yet becomes an oppressor. The parallels to Jim Jones serve as a sobering reminder that such manipulations aren't merely fictional horror scenarios.

Jones began his career claiming to fight racism, building an integrated community that many found genuinely liberating. His religious performances were always a means to a political end. "Religious rhetoric had only ever been a bait-and-switch that would lead his followers to embrace the socialist ideas he'd advocated since his days as a Methodist student pastor in Indiana," explains one historical account.

The parallels between Remmick's fictional predation and Jones's historical abuses highlight a disturbing pattern in American history: the exploitation of marginalized communities' legitimate desires for equality and dignity. Remmick offered freedom from Jim Crow through vampirism. Jones offered escape from American racism through loyalty to his socialist vision. Both promised liberation but delivered death.

Coogler's "Sinners" masterfully examines how predators can weaponize the language of liberation and allyship. As we watch this fictional horror unfold in theaters, we should remember the real people, primarily Black Americans seeking genuine community and equality, who fell victim to Jim Jones's similar predations not even fifty years ago.

Their story reminds us that the most dangerous monsters aren't always fictional.

Before you go, help preserve this history of Jonestown (and similar atrocities committed against the Black community)

If you believe that confronting the truth of our past is essential to any claim this country makes toward justice, then I ask for your support.

Over 21,000 of you have subscribed to this newsletter.

But less than 4% of you are paid supporters.

That makes it hard to keep this going, especially when platforms like TikTok and Instagram are so unstable. I’ve had videos removed, been mass-reported by trolls, and constantly worry about getting shadowbanned or banned completely.

This newsletter is one of the only spaces where I can share these stories without censorship. But I need help to grow it.

📖 If just 5% of you became paid subscribers, I could start bringing on professors, historians, and other experts to unpack these issues in even deeper ways.

🧠 If 10% signed up, I could quit everything else and go full-time — publishing multiple articles a day, covering the latest news and connecting it to the hidden histories they don’t teach in school.

🌎 And if 20% of you subscribed, I could turn this into a platform that lifts up other truth-tellers. Young writers, educators, and creators who are brilliant but have nowhere to share their voice. Especially those from marginalized communities who get ignored by traditional media.

References

Harris, Raquel. "'Sinners': The Meaning Behind the Irish Vampire Remmick." TheWrap, April 25, 2025.

Lawson, Richard. "Sinners Is a Bloody and Bracing Study of History, With Vampires." Vanity Fair, April 10, 2025.

"Race and the Peoples Temple." PBS.org, American Experience.

"Remembering Jonestown 40 Years Later." Rediscovering Black History, November 29, 2018.

"Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple." San Diego State University.

This was a fantastic breakdown of Jones and the horrors he brought to the Black community. He is a Remmik in real life, but way worse. Great job

I remember reading somewhere a description of a white Northern CA semi-hippie who became part of Jim Jones “Church” with his family but separated from them before the exodus to Latin America and mass homicide. I think he lost his wife and children. Unlike the obviously dangerous, armed WACO Cult, few seem to have foreseen his descent into murder. I wish I could find that story.